A flag from South Kalimantan, Indonesia

Provenance research blog #1

In the blog series of the Colonial Collections Consortium, we present a historical object or collection from a former colonial context or situation, currently (or until recently) stored in a museum in the Netherlands that has been the focus of provenance research. With these blogs, we want to give an insight into the importance of provenance research and show the different ways of approaching this type of research. Therefore, each blog explains the steps taken by the respective museum or provenance researcher to carry out the research. Which stories lie behind the object and what can they tell us about the Dutch colonial past?

In focus this time: a flag from Indonesia (formerly known as Dutch East Indies), currently managed by Museum Bronbeek and on loan to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam between 1977 and 2023.

Brief historical background

The flag and its presence in the Netherlands are connected to the Banjarmasin War (1859-1863), which was both a war of succession in the Banjarmasin Sultanate on the island of Borneo and a colonial war for the imposition of Dutch authority. It can be traced back to a military raid on benteng (fortress) Ramonia in South Kalimantan, on 28 September 1861. This was only possible to determine after in-depth provenance research, as existing information was contradictory.

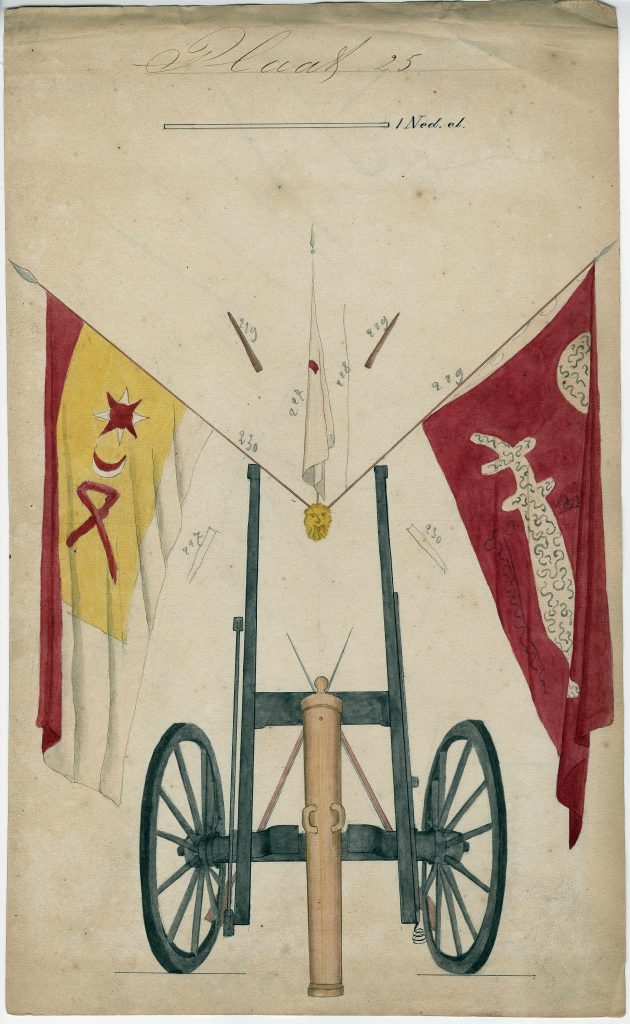

The use of flags in maritime trade, ceremonies and warfare was common in the Indonesian archipelago at that time. Different rulers often carried their own flag with specific meanings, often referencing religious or dynastic allegiances. During battles, they could be spiritually endowed and used to inspire troops. It was often seen as a sign of misfortune when these were damaged or captured. The Dutch were aware of this significance, as shown in attempts at creating inventories of flags in the region. They were often taken from battlefields as symbols of victory. Hence a few dozen flags ended up in the Netherlands and can today be found in Dutch museums.

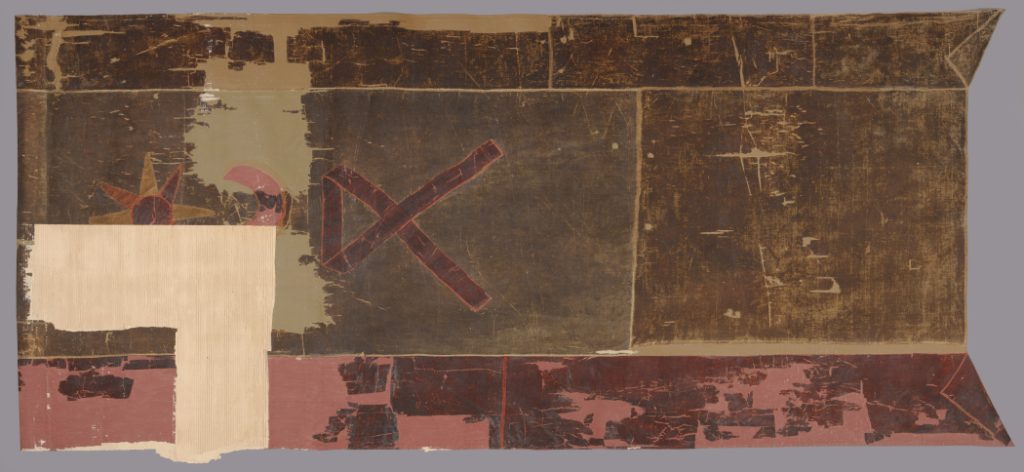

About the flag

This cotton flag (275 x 122 cm) is part of a collection of 27 (fragments of) flags and 25 flagpoles and pikes from the Indonesian archipelago (its inventory number is 1870/10-1-4). Its colours have faded through time; today it is brown-green, decorated with a crescent, an eight-pointed star and a ribbon. In the mid-nineteenth century, the crescent combined with a five- or eight-pointed star was a common symbol in the Islamic world, related to the Ottoman Caliphate. The meaning of the red ribbon is less self-evident. It probably represents a stylised combination of the Arabic letters lam and alif, referring to the first word of the Islamic confession of faith (shahada) or to the name of Allah himself (lam jalalah).

The provenance research

In 2022, research was carried out in the context of the Pilot project Provenance Research on Objects of the Colonial Era (PPROCE) to establish its provenance, including the situation during which it was seized by the Dutch. The choice to focus on this and other Indonesian objects stemmed from a decision made together with the National Museum in Indonesia. This involved carrying out archival research and object analysis, using different materials and consulting with Indonesian historian Mansyur Sammy. The starting point was the museum’s information system and existing archival documentation. It sometimes happens that objects are renumbered and reregistered, leading to mistakes and hence, a longer research time. This was the case of the flag presented here.

The museum documentation indicated that the flag was donated to Museum Bronbeek in 1870 by Lieutenant Colonel C.F. Koch, and that it had been seized from Pangeran Hijdajat (or Prince Hidayatullah), following the conquest of “Fort Romanio” on 28 September 1861. This donation was confirmed in an internal report and mentioned in a newspaper article. However, there were doubts regarding the exact provenance since an 1881 memorial volume about Bronbeek had attributed this flag to the conquest of Lambadak, Aceh, in 1877. Hence it was necessary to carry out additional research about the military context at the time. This required consulting many government archives, including those of the Ministry of the Colonies and the Ministry of War. These showed that the conquest of Ramonia was part of a larger expedition against the Banjarese Prince Antarasi, rather than Prince Hidayatullah, the main contender to the Sultan’s throne. Within the Banjarmasin Sultanate, Antasari, who was of different royal lineage, had supported the first attacks on the Dutch in 1859. Today, he is seen as a National Hero in Indonesia.

On 28 September 1861, Ramonia was attacked by the Dutch. According to this expedition’s report, three yellow flags decorated with a crescent, star and koranic verses waved on the palisades of fortress. These were taken and, although Koch was probably not present, it is very likely that one of them ended up in his possession, since he was the highest in command in the region. Based on the Dutch military sources consulted, it was possible to refute the claim that the flag belonged to Prince Hidayatullah. This erroneous attribution may have been Koch’s mistake, when he donated the flag to Bronbeek, or derived from the fact that the flag was renumbered several times.

Another factor that led to doubts of attribution had to do with the flag itself and was further investigated through object analysis. Through historic descriptions and depictions of the flag (for example, the lithographs in Bronbeek’s 1881 memorial volume), it could be concluded that the current green colour was the result of discolouration of the organic dyes of the flag, and that this was, in fact, one of the three yellow flags captured in 1861. This was further confirmed by historian Mansyur Sammy, who recognized the ribbon on the flag as a common symbol of Prince Antasari.

Reflection

Research about this flag reflects some of the challenges of investigating the provenance of objects in museum collections – for instance, objects might change over time (in this case, the colour), making it difficult to match specific objects with archival information. Furthermore, attributions are sometimes incorrect, due to museum work, such as conservation or relocations, or mythmaking by donators and curators. This blog shows that existing information should not be taken at face value, for in-depth archival research can reveal additional/diverging information. Provenance research is often carried out in the context of debates about and claims for restitution of objects taken in colonial times. Furthermore, and as Hilmar Farid (former director-general of the Indonesian Ministry of Education and Culture) stated in 2021, it is a valuable tool to produce knowledge about history and past injustices. According to Farid, it is essential that joint decisions are made regarding what is to be researched, since the process of dealing with colonial collections is also about building relationships between people of different countries (in this case, Indonesia and the Netherlands) and a common understanding of the past. He referred then to the flag presented here as an important object not for its aesthetic value, but for what it signified to people in the past.

Final words

To better understand the historic and current meanings of objects, and how to ethically care for them, information about their origin and acquisition histories are essential. Provenance research is an ongoing process for museums. The Colonial Collections Consortium supports institutions that manage collections with this work by sharing knowledge and information, and by offering stakeholders a network. Would you like to know more or share information with us? Please contact us!

References and further reading

The provenance research presented in this blog was carried out by Klaas Stutje of the NIOD (Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies) and the report can be found here (see number 26). The information presented in this blog derives from this report, as well as the PPROCE report and email communication with Klaas Stutje. Hilmar Farid’s comments were derived from the recording of “The Politics of Restitution”, an online event organised by the SOAS University of London in 2021.