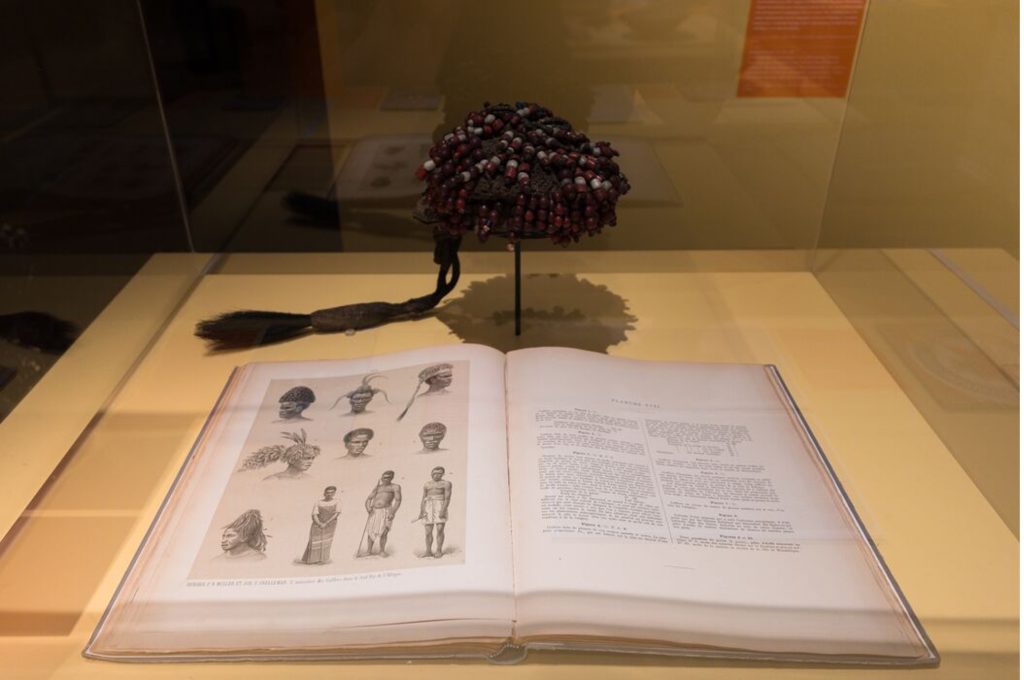

A beaded headdress from Mozambique

Provenance research blog #3

In the blog series of the Colonial Collections Consortium, we present a historical object or collection from a former colonial context or situation, currently (or until recently) stored in a museum in the Netherlands that has been the focus of provenance research. With these blogs, we want to give an insight into the importance of provenance research and show the different ways of approaching this type of research. Therefore, each blog explains the steps taken by the respective museum or provenance researcher to carry out the research. Which stories lie behind the object and what can they tell us about the Dutch colonial past?

In focus this time: a beaded headdress from Mozambique in the collection of Wereldmuseum Rotterdam.

An “invisible empire”: brief historical background

Cultural objects in Western museums which were collected or looted in a colonial context contain many – sometimes little-known – stories about this period. Provenance research is a valuable tool that helps bring these stories to light. However, it can’t provide all the answers and often raises new questions. Making knowledge about collections available is important, as it allows for a better understanding of museum collections and makes it possible for countries and communities of origin to locate their cultural heritage.

This is particularly relevant when dealing with collections that one might not expect to find in Dutch museums, such as the many objects from the African continent. The beaded headdress looted in Mozambique in 1884 and addressed in this blog is a good example. By the late nineteenth century, the Netherlands no longer possessed colonies in Africa, yet it still participated in and profited from European exploitation of African labour and natural resources. At this time there were hundreds of Dutch trading posts across the continent, around 10 of which were in Mozambique, then a Portuguese colony. Provenance researcher François Janse van Rensburg refers to this as an “invisible empire” of Dutch trade in Africa.

Today, the Wereldmuseum contains thousands of objects from Africa, sent to the Netherlands by employees of Dutch trading companies, such as the Nieuwe Afrikaansche Handels-Vennootschap (NAHV), the Oost-Afrikaansche Compagnie (OAC), and Hendrik Muller & Co. Many of these objects – including the headdress – were brought by the directors and employees of these companies. One such collector was Hendrik Muller (1859-1941). The Muller family was deeply involved in commercial activities in Central and Southern Africa, including these companies. Hendrik Muller also participated in the Berlin conference in 1884-1885, where the African continent was divided amongst European powers. Alongside trade, Muller’s father was one of the co-founders of the Wereldmuseum Rotterdam. Muller himself, during his time as co-director of the OAC, became interested in anthropology during a visit to Mozambique where he acquired many objects for the museum.

The provenance research

Provenance research is sometimes carried out in the context of requests for restitution, as shown in blog #2. In other cases, such as the flag in blog #1 or the Mozambican headdress, it is driven by research questions. The research presented here and carried out by Janse van Rensburg started with a book, ‘Industrie…du sud-est de l’Afrique’. Written at the end of the nineteenth century by Hendrik Muller and anthropologist Johannes Snelleman, it contains ethnographic descriptions mainly of Mozambique and features illustrations of objects, including the headdress. It describes the headdress and the materials it is made of (such as cotton, beads, cowries, the tail of a wild animal). A footnote clarifies that it would have been worn by a Massingire priest and that it was taken during a war. Janse van Rensburg aimed to understand what the Dutch were doing in Mozambique at the time and how this object ended up in the Netherlands.

The research followed the usual steps. First, consulting the information available in the museum. This included the inventory card, which indicated that it was donated in 1885 by M.H. Maas, a Dutch consul in Quelimane in Mozambique, and employee of the OAC. Janse van Rensburg searched the museum’s archive and found a letter that was connected to this donation. Written by Hendrik Muller and addressed to the then director of the recently founded Museum for Land and Ethnology in Rotterdam (later Wereldmuseum), the letter claimed that it had been worn by a spiritual leader during a ritual that preceded a revolt of the Massingire people in 1884 in the Zambezi River region in Mozambique.

The Massingire War of 1884 was one of the first anti-colonial rebellions against Portuguese colonialism in Mozambique. It took place in the context of intensifying colonialism by European powers around the time of the Berlin conference. This intensification involved annexation of territory, exploitative taxes, and a ban on Massingire religious practices leading to the 1884 revolt. The revolt soon turned into a general uprising, with rebels targeting Dutch, French, and Portuguese commercial enterprises (such as trading posts and opium plantations) which made their incomes through exploiting the local peoples.

While many items acquired by Muller and other collectors were bought from local populations in what today would be seen as tourist markets, others were obtained through theft and looting. Considering the archival materials available, it was possible to conclude that it was most likely looted in the context of this conflict.

Reflection: an unfinished process

Because all archival sources used for the research were European, many questions remain to be answered: who were the Massingire? Who wore the headdress and for what purpose? Might the headdress still hold meaning for people today? What does this looted object say about other objects which were not looted, but collected in the same context of colonial exploitation (such as this tablecloth from Mozambique)? This reveals the limits of archival-based research. To answer these questions, more time and (financial) resources would be required to seek collaborations with researchers in Mozambique and carry out fieldwork. With so many objects to be studied, provenance researchers often need to limit their focus to understanding how an object was appropriated and ended up in the museum.

For this reason, provenance research can often be seen as an unfinished process. Hence it is important to make the existing knowledge publicly available, for instance, through publications, presentations or exhibitions. The research carried out by Janse van Rensburg has been published and is currently shown in the exhibition “Unfinished past: return, keep, or…?” at Wereldmuseum Amsterdam, which is part of the Pressing Matter project. This exhibition dives into the current debate on restitution and critically explores the ways in which objects from colonial contexts entered the collections of European museums (and this one in particular), including through trade, scientific expeditions, diplomatic gifts, missionary work or colonial conquest.

The headdress is used there as an example of an object acquired through Dutch colonial trade, as well as to show the connections between trade and conflict. Furthermore, the results of the provenance research are presented on a touchscreen, amongst other provenance histories. Through photographs, letters and other archival materials consulted for the research, the headdress sheds light on the histories of the Dutch “invisible empire” in Africa.

The exhibition also raises questions about possible next steps – what to do with an object that is known to be looted, yet where knowledge – and potential interests – of the community of origin are missing? Hopefully sharing this knowledge will lead others to pick up where this research ended, to dig deeper into the histories and meanings contained in this and many other cultural objects and belongings in Dutch museums.

Final words

To better understand the historic and current meanings of objects, and how to ethically care for them, information about their origin and acquisition histories are essential. Provenance research is an ongoing process for museums. The Colonial Collections Consortium supports institutions that manage collections with this work by sharing knowledge and information, and by offering stakeholders a network. Would you like to know more or share information with us? Please contact us!

References and further reading

The provenance research presented here was carried out by François Janse van Rensburg of Wereldmuseum in the context of the Pressing Matter project. This research is currently presented in the exhibition Unfinished Pasts at Wereldmuseum Amsterdam and was published in REALMag #10 (2025). A more in-depth article about the headdress and its provenance will soon be published in an upcoming publication of Pressing Matter.