Provenance research blog #2

In the bimonthly blog series of the Colonial Collections Consortium, we present a historical object from a former colonial context or situation, currently stored in a museum in the Netherlands that has been the focus of provenance research. With this blog, we want to give an insight of the importance of provenance research and show the different ways of approaching this type of research. Therefore, each blog explains the steps taken by the respective museum or provenance researcher to carry out the research. Which stories lie behind the object and what can they tell us about the Dutch colonial past?

In focus this time: seven Tigua sacred ‘objects’ of the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo community, United States.

Brief historical background

The Ysleta del Sur Pueblo (or YDSP) is a federally recognized Native American tribe in El Paso, Texas. The Tigua people (pronounced Tiwa) of YDSP were deeply impacted by Spanish and later US colonialism. In 1680, following a revolt against Spanish rule, they were forcibly relocated from New Mexico to Texas. In the nineteenth century, they, like many other Native American tribes, were driven to extreme poverty due to the appropriation of their land and resources by both the US and state governments. It was in this context of duress that the objects were bought in 1882 by the Dutch anthropologist Herman Frederik Carel Ten Kate jr., during an expedition to study Native Americans. This acquisition was done at the request of Lindor Serrurier, the then director of the National Ethnographic Museum (a precursor of Wereldmuseum Leiden), using Dutch government funding.

In 2024, the YDSP Pueblo, with the support of the US government, submitted a restitution request to the Dutch government. In question were five (and ultimately seven) objects managed by Wereldmuseum Leiden. This request argued that since these are ceremonial and spiritually important representations of the culture and faith of the Pueblo, they should be returned. Following this request, Wereldmuseum carried out provenance research about the objects, leading to the conclusion that their transfer to the Netherlands and this museum in 1883 represented a case of involuntary loss.

About the Tigua ceremonial ‘objects’

The seven objects – the fragment of a headdress, two drums and respective drumsticks, three rattles, a shield, and moccasins – constitute sacred, communally owned belongings of the Tigua people of YDSP. Of particular importance are the double-headed drum and drumstick, which is believed to be the twin of the Pueblo’s remaining ceremonial drum. According to tradition, both were made from the same tree 350 years ago in New Mexico, before the Tigua’s exile to El Paso. The restitution claim of 2024 noted the drum’s importance to the ceremonial cycle and its connection to the Winter clan (now the Pumpkin and Corn villages), while the remaining drum belonged to the Summer clan. Without the Winter clan’s drum, the Summer clan’s drum is used for both summer and winter dances.

The current “restitutionary conjuncture”

The Tigua’s first official request for repatriation was made by the Tribal Council of Ysleta del Sur Pueblo in 2014, although the Tribal Council claims there were earlier requests, dating back to 1967. This request was rejected by Wereldmuseum on the basis that the objects had been legally sold. While several meetings and negotiations between the Tribal Council and the museum followed this decision, effective change only took place in 2024.

In recent years, important steps have been taken in the Netherlands and beyond towards the development of restitution policies, making it possible to speak of the current moment as a “restitutionary conjuncture”, to quote provenance researcher Klaas Stutje (2025). More specifically, in 2021, the Dutch government published its policy vision on collections from a colonial context, followed in 2022 by a Letter to Parliament on its implementation. Since then, a few hundred historical objects have been returned, mainly to Indonesia and Sri Lanka.

The provenance research

Following the 2024 restitution request, the Wereldmuseum conducted provenance research on the Tigua’s sacred artefacts. The research and resulting report focused on 1) the history of the YDSP to better understand the context during which the objects had been collected; 2) Ten Kate’s expedition to North America in 1882-83, to understand the role played by the Dutch government and museum in this expedition, as well as the anthropologist’s collecting practices; 3) Ten Kate’s visit to YDSP and the seven objects; and 4) the history of the relationship between Wereldmuseum and Pueblo.

The first point was answered mainly using secondary resources. The second and third points involved analysing the correspondence related to the financing by the Dutch government of the purchase of objects by Ten Kate and his donation of those objects to the museum in 1883. The museum’s inventory cards and a travel report by Ten Kate included important information that detailed Ten Kate’s use of unethical acquisition methods, involving coercion, threats and bribery. His travel report mentioned the objects and suggested that the sale by War Captain Bernardo Holguin had not been entirely voluntary, since on the following day, Holguin expressed remorse about this sale and tried to reverse the transaction.

Information shared by representatives of YDSP in the context of recent dialogues with Wereldmuseum and the 2024 restitution claim also offered vital information about the acquisition context, leading to a more critical and context-sensitive understanding of the conditions in which the objects were taken. Of particular importance were the arguments that Holguin had been coerced by Ten Kate to sell the objects, that his willingness to sell sacred communal artefacts was due to the extreme poverty experienced in YDSP at the time, and that Holguin was in fact not authorized to sell these since he didn’t own then but rather managed them for the community. This information was central to the final decision regarding the restitution claim.

Reflection

The provenance research showed that the acquisition of the objects in 1882 was against the wishes of YDSP, even if it resulted from the sale of the items by a member of the community. Dialogue with the community in more recent years – and mainly in the context of the restitution requests – reiterated this fact and emphasized the ongoing importance of these objects to the Tigua’s ceremonies and rituals. This reexamination of the historical context in which the objects were acquired offers an important example of how complex it is to accurately assess the conditions and power (dis)balances in place when objects are collected or seized, without disregarding the agency of the original owners. Crucially, it shows that provenance research and a critical understanding of historical and cultural circumstances should, as much as possible, result from an open and reciprocal dialogue between museums and the communities of origin.

Final words

In response to the restitution request by the US and YDSP, and on the advice of the independent Colonial Collections Committee (in line with the Dutch Policy vision on collections from a colonial context), the Dutch Minister of Education, Culture and Science Eppo Bruins decided in early 2025 to return the seven objects unconditionally. A ceremony to mark this return took place on 20 March 2025 at Wereldmuseum Leiden (see photograph).

To better understand the historic and current meanings of objects, and how to ethically care for them, information about their origin and acquisition histories are essential. Provenance research is an ongoing process for museums. The Colonial Collections Consortium supports institutions that manage collections with this work by sharing knowledge and information, and by offering stakeholders a network. Would you like to know more or share information with us? Please contact us!

References and further reading

The provenance research presented here was carried out by provenance researcher François Janse van Rensburg (Wereldmuseum). The report and the advice of the independent Colonial Collections Committee can be found here. The information presented in this blog derives from this report, as well as email communication with François Janse van Rensburg. More information about the return of the seven objects can be found on the websites of the Dutch government and of Wereldmuseum. For more information about the Dutch policy for dealing with collections from a colonial context, please see the website of the Colonial Collections Consortium.

Provenance research blog #1

In the bimonthly blog series of the Colonial Collections Consortium, we present a historical object from a former colonial context or situation, currently stored in a museum in the Netherlands that has been the focus of provenance research. With this blog, we want to give an insight of the importance of provenance research and show the different ways of approaching this type of research. Therefore, each blog explains the steps taken by the respective museum or provenance researcher to carry out the research. Which stories lie behind the object and what can they tell us about the Dutch colonial past?

In focus this time: a flag from Indonesia (formerly known as Dutch East Indies), currently managed by Museum Bronbeek and on loan to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam between 1977 and 2023.

Brief historical background

The flag and its presence in the Netherlands are connected to the Banjarmasin War (1859-1863), which was both a war of succession in the Banjarmasin Sultanate on the island of Borneo and a colonial war for the imposition of Dutch authority. It can be traced back to a military raid on benteng (fortress) Ramonia in South Kalimantan, on 28 September 1861. This was only possible to determine after in-depth provenance research, as existing information was contradictory.

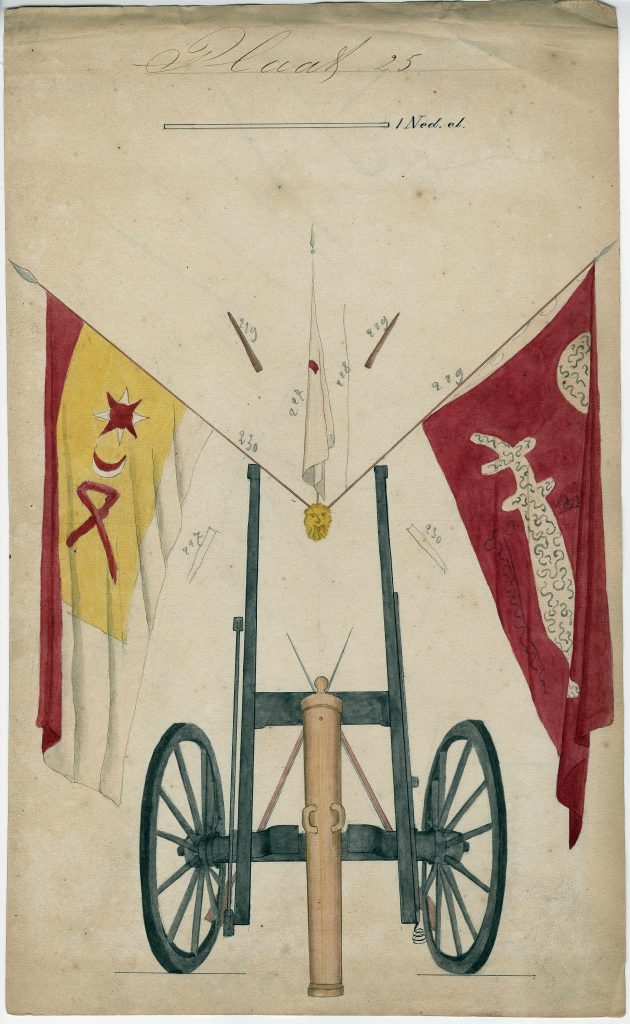

The use of flags in maritime trade, ceremonies and warfare was common in the Indonesian archipelago at that time. Different rulers often carried their own flag with specific meanings, often referencing religious or dynastic allegiances. During battles, they could be spiritually endowed and used to inspire troops. It was often seen as a sign of misfortune when these were damaged or captured. The Dutch were aware of this significance, as shown in attempts at creating inventories of flags in the region. They were often taken from battlefields as symbols of victory. Hence a few dozen flags ended up in the Netherlands and can today be found in Dutch museums.

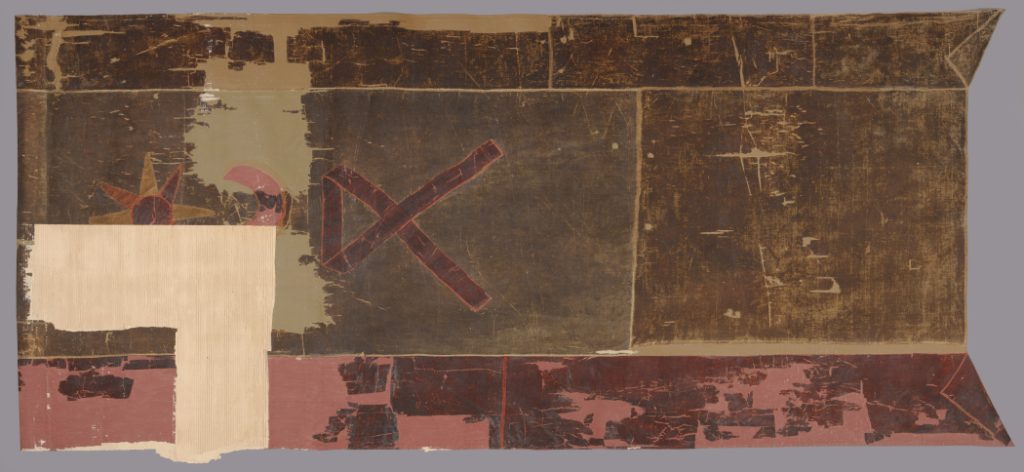

About the flag

This cotton flag (275 x 122 cm) is part of a collection of 27 (fragments of) flags and 25 flagpoles and pikes from the Indonesian archipelago (its inventory number is 1870/10-1-4). Its colours have faded through time; today it is brown-green, decorated with a crescent, an eight-pointed star and a ribbon. In the mid-nineteenth century, the crescent combined with a five- or eight-pointed star was a common symbol in the Islamic world, related to the Ottoman Caliphate. The meaning of the red ribbon is less self-evident. It probably represents a stylised combination of the Arabic letters lam and alif, referring to the first word of the Islamic confession of faith (shahada) or to the name of Allah himself (lam jalalah).

The provenance research

In 2022, research was carried out in the context of the Pilot project Provenance Research on Objects of the Colonial Era (PPROCE) to establish its provenance, including the situation during which it was seized by the Dutch. The choice to focus on this and other Indonesian objects stemmed from a decision made together with the National Museum in Indonesia. This involved carrying out archival research and object analysis, using different materials and consulting with Indonesian historian Mansyur Sammy. The starting point was the museum’s information system and existing archival documentation. It sometimes happens that objects are renumbered and reregistered, leading to mistakes and hence, a longer research time. This was the case of the flag presented here.

The museum documentation indicated that the flag was donated to Museum Bronbeek in 1870 by Lieutenant Colonel C.F. Koch, and that it had been seized from Pangeran Hijdajat (or Prince Hidayatullah), following the conquest of “Fort Romanio” on 28 September 1861. This donation was confirmed in an internal report and mentioned in a newspaper article. However, there were doubts regarding the exact provenance since an 1881 memorial volume about Bronbeek had attributed this flag to the conquest of Lambadak, Aceh, in 1877. Hence it was necessary to carry out additional research about the military context at the time. This required consulting many government archives, including those of the Ministry of the Colonies and the Ministry of War. These showed that the conquest of Ramonia was part of a larger expedition against the Banjarese Prince Antarasi, rather than Prince Hidayatullah, the main contender to the Sultan’s throne. Within the Banjarmasin Sultanate, Antasari, who was of different royal lineage, had supported the first attacks on the Dutch in 1859. Today, he is seen as a National Hero in Indonesia.

On 28 September 1861, Ramonia was attacked by the Dutch. According to this expedition’s report, three yellow flags decorated with a crescent, star and koranic verses waved on the palisades of fortress. These were taken and, although Koch was probably not present, it is very likely that one of them ended up in his possession, since he was the highest in command in the region. Based on the Dutch military sources consulted, it was possible to refute the claim that the flag belonged to Prince Hidayatullah. This erroneous attribution may have been Koch’s mistake, when he donated the flag to Bronbeek, or derived from the fact that the flag was renumbered several times.

Another factor that led to doubts of attribution had to do with the flag itself and was further investigated through object analysis. Through historic descriptions and depictions of the flag (for example, the lithographs in Bronbeek’s 1881 memorial volume), it could be concluded that the current green colour was the result of discolouration of the organic dyes of the flag, and that this was, in fact, one of the three yellow flags captured in 1861. This was further confirmed by historian Mansyur Sammy, who recognized the ribbon on the flag as a common symbol of Prince Antasari.

Reflection

Research about this flag reflects some of the challenges of investigating the provenance of objects in museum collections – for instance, objects might change over time (in this case, the colour), making it difficult to match specific objects with archival information. Furthermore, attributions are sometimes incorrect, due to museum work, such as conservation or relocations, or mythmaking by donators and curators. This blog shows that existing information should not be taken at face value, for in-depth archival research can reveal additional/diverging information. Provenance research is often carried out in the context of debates about and claims for restitution of objects taken in colonial times. Furthermore, and as Hilmar Farid (former director-general of the Indonesian Ministry of Education and Culture) stated in 2021, it is a valuable tool to produce knowledge about history and past injustices. According to Farid, it is essential that joint decisions are made regarding what is to be researched, since the process of dealing with colonial collections is also about building relationships between people of different countries (in this case, Indonesia and the Netherlands) and a common understanding of the past. He referred then to the flag presented here as an important object not for its aesthetic value, but for what it signified to people in the past.

Final words

To better understand the historic and current meanings of objects, and how to ethically care for them, information about their origin and acquisition histories are essential. Provenance research is an ongoing process for museums. The Colonial Collections Consortium supports institutions that manage collections with this work by sharing knowledge and information, and by offering stakeholders a network. Would you like to know more or share information with us? Please contact us!

References and further reading

The provenance research presented in this blog was carried out by Klaas Stutje of the NIOD (Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies) and the report can be found here (see number 26). The information presented in this blog derives from this report, as well as the PPROCE report and email communication with Klaas Stutje. Hilmar Farid’s comments were derived from the recording of “The Politics of Restitution”, an online event organised by the SOAS University of London in 2021.